Memories of the Sepoy Mutiny, Chikankari, and something for the palate.

This story first appeared in Mint on April 13, 2017 under the section ‘Weekend Vacations’.

___________________________________________________________________________

The chota imambara.

Nostalgia is a formidable force when combined with a love for travel. Lucknow had been on my mind for a long time. I had first travelled to the city more than a decade ago and still remember how awe-struck I was.

Lucknow holds a special place in the hearts of food lovers (think kebabs and biryani but also vegetarian delicacies) and architecture enthusiasts. On my second trip to the Uttar Pradesh capital, I wanted to go off the beaten track and explore the lesser-known aspects of this much feted city.

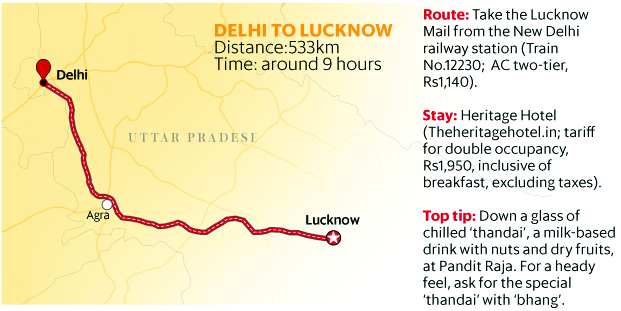

I took the Lucknow Mail from the New Delhi railway station on a Friday night, reaching the Charbagh railway station early next morning. During the short cycle-rickshaw ride to the atmospheric Heritage Hotel, I watched the city stir into action.

After a leisurely shower and breakfast, I took an autorickshaw to Khadra, a hub for Chikan embroidery. I sought out Sameena Bano, an artisan who works with Tanzeb, a Chikankari label. Over the next few hours, she told me all about the little-known details of this craft—all the while keeping her head down, stitching intricate patterns on colourful fabric. This method of hand embroidery, which has existed since the time of the Mughals, features subtle floral motifs that are best suited for garments of pastel shades.

Bidding goodbye to Sameena Bano, I headed to some of the signature structures of Lucknow. The Bara and Chota Imambara, Shahi Bouli, Asafi Masjid and Rumi Darwaza, all built by the nawabs, are still veritable icons that made me veer slightly from the “off-beat” nature of my trip. I wanted to quickly swing by these spots and reserve the next day for a tryst with colonial history, one that is often overlooked by travellers.

Next morning, then, it was time to visit the Residency, a complex of buildings that includes the palatial 18th century residence of the erstwhile British resident (an official who oversaw the affairs of the province of Awadh on behalf of the Raj).

Paying an entry fee of Rs5, I found myself in a sprawling green lawn. Cutting through the middle was a paved path that led to the imposing Bailey Guard Gate, which gets its name from John Bailey, one of the British residents of Awadh. Emerging on the other side of this gate, I spotted the ruins of several buildings spread out haphazardly. For a moment, they reminded me of giant Lego blocks made of brick and stone. I could see deep scars on the walls and gaping holes where there should have been roofs. Doors and windows were missing.

Lucknow played an important role in India’s First War of Independence (also known as the Sepoy Mutiny) in 1857. A large number of Indian soldiers rebelled against the British, leading to a series of bruising battles. Some of the action took place at the Residency too, with the buildings being shelled heavily. The broken buildings I was looking at were stark reminders of those times.

I meandered from one broken building to another: a memorial dedicated to British martyrs, the kitchen, the house of the resident surgeon, and a banqueting hall. My last stop was a museum that houses photographs, documents and other memorabilia of British rule.

It was 2pm, the time had flown. And all that history-hunting had left me ravenous. Some of the famed Lucknowi tahiri (the local, vegetarian counter to the biryani) followed by kulfiwould do the trick.