Fort Kochi, the most interesting part of Kochi city in central Kerala, deserves your attention. To me, it is one of the most interesting parts of Kerala, infinitely more interesting than Ernakulam, its cousin across the bay. Ernakulam is your regular Indian city, forever caught in an urban tizzy. It has lost much of its cultural identity and sanity over the past two decades.

Fort Kochi, on the other hand, is a different world; an oasis of cultural and historical riches that soothe the soul of the discerning traveler. Here, you will find a co-mingling of several histories, because a number of dynasties and communities have left their imprint on this tiny piece of land.

For many centuries, Kochi was ruled by several native Malayali chieftains and kings. It is a documented fact that Kochi state was formed in 1142 AD, when the kingdom of the erstwhile ruler Kulasekhara, broke up. Not much is however known about this kingdom until the late fifteenth century, when Vasco da Gama landed on the coast of Calicut.

Fort Kochi came into existence only after the arrival of the Portuguese in India. A few years after they made landfall on the Calicut coastin 1498, they ventured south and built a settlement on a land parcel gifted to them by the then king of Kochi. Their interests lay mainly in trade. They were keen to ship back pepper and other spices. Soon after they reached Kochi, they fortified it with permission from the Kochi Raja and named it Fort Emmanuel. When the modern city of Kochi was formed much, much later, Fort Emmanuel was renamed Fort Kochi. Except for a bastion and a cannon (which you’d be hard put to find), nothing remains of the fort today. But the town has emerged into a vibrant tourist destination.

I give you five specific reasons why you should go there right away.

One: the Portuguese heritage and the churches

The Portuguese were aggressive conquistadors. At the same time, they were prolific builders too. Wherever they went, they put up all manner of beautiful structures – including stately mansions, churches and forts. Fort Kochi is a superb example of the architectural legacy of the Portuguese.

I love two things the most. The first is the way in which they beautifully blended Portuguese and European sensibilities with the native Keralan architectural style. And so, you will find tall columns, arches and gables in houses that are roofed with local tiles. And since no house in Kerala is deemed complete without a backyard and a well, you will find a lush backyard and a deep well too.

Stroll along the streets of Fort Kochi and you will see what I mean. Several of these buildings have been converted into cafes, art galleries and guest houses, which is great. It means that tourism is being built on the strong foundation of a heritage conserved. Bishop’s House, Cabral Yard, Bastian Bungalow and several hotels around the Vasco da Gama Square are fine examples of Indo-Portuguese architecture.

The other thing I love about the Portuguese are their churches. Here, you will find solid masonry, tall spires and belfrys, exquisite stained glass, unshakeable wooden furniture and beautiful murals and frescoes.

Fort Kochi has the best collection of medieval churches in India, all within a few miles of one another. From the church where Vasco da Gama was first interred after his death (St. Francis Church, 1516 AD) to Santa Cruz Basilica (1505 AD), Our Lady of Life Church (1650 AD), Our Lady of Hope Church (Vypin, 1605 AD) are some of the best churches I have been to. It is a pleasure to sit in the pews in silence for a bit, then gaze up at the murals, take in the liturgical furniture and finally, stroll around in the church yard. I get goosebumps when I find tombstones dating back to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Speaking of churches, Fort Kochi has one of the most intriguing museums I have ever seen. The Indo-Portuguese Museum is located inside the compound of Bishop House and contains a number of rare artefacts from the Portuguese era. With one important twist: these artefacts are all liturgical in nature; which means, they pertain to the history of the Catholic Church in India. From medieval versions of the Bible, chalices, crosses, altars and vestments, they are all on display here. If you love love the intersection of history and religion, you will love this museum for sure.

Two: the beaches

Fort Kochi is located bang by the sea. It is home to a few lovely beaches where the sand is golden brown and very clean. Apart from what is known as the Fort Kochi beach, there is a beach in Vypin and another in Cherai. Fort Kochi beach does get crowded in the evening, but you can still have a lot of fun. The crowd is never troublesome. Cherai and Vypin beaches are lesser known and therefore, much less crowded. You have to be very careful though, because the waters are very rough. We have built sand castles, jogged on the wet sand and played Frisbee here.

Being on the West coast, these beaches give you great views of sunset. Finish frolicking in the water by 5:30 pm or so, and then settle down on the sands. Watch the sun slowly sink into the horizon. The orange and pink glow it casts on the waters is magical indeed! Words have no place at moments like these. I love basking in this fading glow. At times like this, I truly feel one with the universe.

Three: the food and the restaurants

Where there is the sea, there is bound to be excellent seafood. And so it is with Fort Kochi. Eateries here offer you a wide variety of fish, in addition to prawns, squids and crabs. And you can have them fried or curried, cooked in one of several ways in the traditional Kerala style.Pair these dishes with the flaky, crisp Kerala porotta or dosaiand you will reach heaven in this life itself.

Or, you could order a naadan (‘country/local/traditional’ in Malayalam) meal, which is served on a plantain leaf, and ask for a non-vegetarian dish on the side. The meal, known as ‘oonu’ in Malayalam, typically consists of two or three vegetable preparations (such as avial, thoran, kaalan, etc.), sambar, rasam, spiced buttermilk, papad, banana chips and pickle, all this to be eaten with nutrient-rich parboiled rice. Some restaurants add a few other items to this ensemble.

My preferred place for lunch or dinner is a sea-fronting restaurant with excellent views of the harbor and the bay. To eat and drink while watching boats and mammoth ships pass by is an interesting experience, to say the least. Seagull Restaurant on Calvathy Road is my all-time favourite for a beer and meal.

For breakfast, stick to delicious local food options like puttu, appam and dosai, served with kadala curry, meen curry or vegetable stew. My kind of breakfast is eaten steaming hot at a street cart, with the aroma of the food mingling with the chatter of locals who are digging in before plunging into their workday.I love to end the meal with a cup of strong Kerala style tea.

Though some eateries serve Continental food and noodles too, I give these a wide berth, because they don’t make it well. It just seems to be a pretence to serve foreign tourists.

Four: the atmospheric hotels

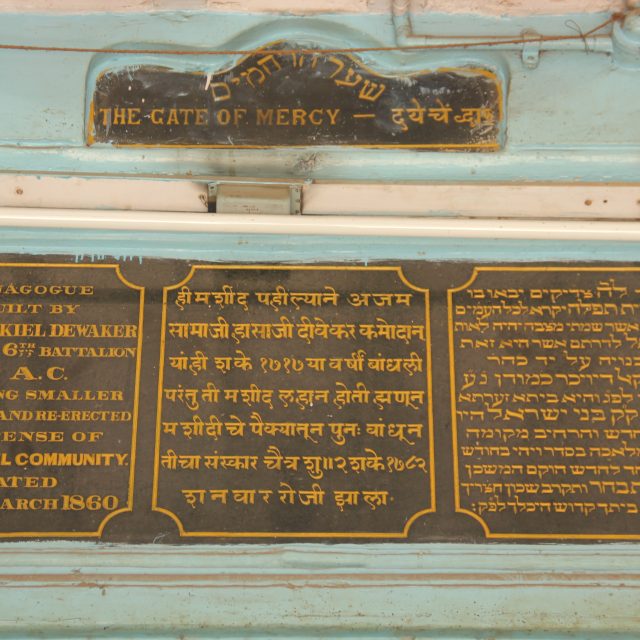

Nowhere else (at least in India) have I seen so many lovely, centuries-old buildings that have been converted into hotels, B&Bs and guest houses. And each one of these buildings has many tales to tell. Koder House, for instance, belonged to a Jewish family in the 19th century, before it was sold by the last descendent. It is now the lovely hotel with a red façade on Vasco da Gama Square. Old Lighthouse Bristow Hotel was the site of the old lighthouse of Kochi and the residence of a senior official of the British empire. The Old HarbourHotel belonged to the Dutch way back in the eighteenth century. I could go on like this.

These hotels are high on history and atmosphere, something you’d not find in a regular hotel.

Five: the native art forms of Kerala

Take in a cultural performance at the Kerala Kathakali Centre, located in a tiny winding lane near the Santa Cruz Basilica. A few months back, I spent an enchanting evening watching a Kalaripayittu performance, an ancient martial art form of Kerala. The Centre hosts vocal and instrumental concerts and Kathakali recitals also.

Another venue for such performances is Greenix, which has two auditoria. One of them is located near the bus stand and across from the boarding point for the ferries to Vypin (don’t ask me why, but these ferries are called ‘Jhankar’). Greenix’s second centre is located onCalvathy Road, near a landmark building called Pepper House.

When you are there….

- Hop onto the large motorized barge, locally known as ‘Jhankar’ and take a five minute ride to the island of Vypin. Once there, take an auto or a bus to the lighthouse and beach.

- From Vypin bus stand (which is close to where the Jhankar will drop you), you can take a bus to Cherai junction and from there, hop into an auto to go to Cherai beach. If you don’t like buses much, you could take an auto from Vypin bus stand itself. The ride to Cherai will take between half an hour and 45 minutes. Cherai beach is unspoilt, clean and not crowded on most days.

- From Vypin, you could take an auto or bus to Vallarpadam island and visit the beautiful medieval church there.

- If you are interested in railway history and trivia, you should visit Cochin Harbour Terminus on Willingdon Island. Until about 1997, long distance express and freight trains used to ply from here. But dwindling business on this route sealed the fate of the terminus. Today, this small abandoned railway station holds a thousand memories and stories. An old weighing machine, fare lists, train schedules, railway tracks, a ticket window…..all these stand mute witnesses to the passage of an era.

- I’d also recommend a visit to the Cochin Marine Museum (Willingdon Island), Jew Town and the spice market (both in Mattancherry).

- And of course, of course, you must visit the Chinese fishing nets. If you go about 5:30 or 6 am, you can watch the fishermen operate it and cast their nets. It is believed that Chinese traders erected these cantilevered nets a few centuries ago. Little would they have guessed that these nets would one day become the most iconic symbol of Fort Kochi.

The vitals

Getting there: Fly to Kochi International Airport and take a taxi to Fort Kochi from there. Or, take a train to Ernakulam from wherever you live. From Ernakulam, take an auto or a bus for an overland ride to Fort Kochi. A more interesting way, however, is to take an auto to the Ernakulam boat jetty and hop onto a public ferry from there.

Shacking up: Like I mentioned earlier, Fort Kochi doesn’t want for accommodation options. From backpacking hostels to luxury hotels, you will find everything here. I think the most interesting way of experiencing the place is to plump for a seaside luxury hotel (high priced, obviously) or a homestay (mid-priced). The Old Lighthouse Bristow Hotel is one of the best luxury hotels I have stayed at. A sea-facing restaurant, an al-fresco lounge, a swimming pool and lovely old-fashioned rooms make this a charming place. The food and service are very good too (in particular, the enormous breakfast that is part of the room tariff).

From many forays to Fort Kochi though, I know that the following are also excellent options:

Koder House(luxury; not seaside, but near the sea and the Chinese fishing nets)

The Cochin Club (mid-priced, but very comfortable and almost luxurious)

Tower House Hotel (luxury; not seaside but near the sea and the Chinese fishing nets)

Brunton Boatyard Hotel (luxury, seaside)

Vintage Inn (at Jnaliparambu Junction; low-priced, but clean and comfortable)

Happy Camper (at Jnaliparambu Junction; a backpacker’s hostel)

Grub

Here is some more dope, beyond what I have told you above. A couple of my favourite eateries here are:

Seagull: seaside restaurant and bar, best known for its Kerala style food. Try to go at around 5:30 pm and catch a table on the re-purposed boat pier. Sit back for the next few hours and watch myriad interesting sights as you guzzle cold beer and enjoy your food. It is not everyday that you get to have a beer watching a glorious sunset or a mother of a ship pass close by.

Shanu’s food cart: This is where you should go, for a cheap, authentic, delicious local-style breakfast. The cart is permanently stationed adjacent to the Tower House Hotel on Vasco da Gama Square. You will invariably find a crowd here from say 6 am every morning. Gorge on puttu, appam, kadala curry and meencurry. Once you reach the Square, ask a local to direct you to Shanu’s thattukada (‘thattukada’ is Malayalam for food cart).

Getting around

This settlement is small enough (and of course beautiful enough) to cover on foot. This is how I move around whenever I am there. Other good option is to hire a cycle or scooter by the day. Auto rickshaws (known as tuktuks in certain countries) are available too.

Since Kerala is a conservative state, please cover up adequately.Since the weather is extremely hot and humid for six months a year, light, summery clothes would be your best bet.

With the influx of foreign tourists, some local eateries/bars.auto drivers have started acting snooty towards Indian tourists. Which is sad. I have encountered such specimens a few times. So, if you are an Indian visiting this place, be warned. Remember to not take it personally. If you find someone behaving unreasonably, just give him a piece of your mind (politely, but firmly) and move on to another auto, eatery, hotel. There are plenty of options.

When to go

The heat here is torrid from March to June. If you go during these months, you can roam around in the morning and evening, and retreat to your room in the afternoon.

The best time is from mid-June to mid-August (when the place is drenched by the monsoon rains) and from November to February (when the weather is somewhat pleasant).

Show me some love. Like and share this post.