The story behind Mumbai’s Jewish connection. And how Masjid Bunder railway station got its name.

_______________________________________________________________________

I stumble out of the packed Central Railway local train at the Masjid Bunder station. As it always happens with me when I alight from a local train in Mumbai, I remain dazed for a few minutes as I try to get my bearings. Being packed like a sardine for more than an hour leaves my hair and my wits askew.

Crossing the narrow foot over bridge on the Eastern side, I descend into the crowded bylanes of Mandvi. All around me, vegetables and other goods are being loaded onto or unloaded from trucks. Cycles and scooters are parked haphazardly. Stalls selling samosas, vada pav, lassi and lemon juice dot the lanes here and there. Pedestrians rush past, elbowing you aside, as they always do in this thrusting, frenetic city.

It is the fag end of May and the air is smothering me like a hot, wet blanket. This is Mumbai at its humid worst, but the good news is that in a couple of weeks or so, the monsoon will start. And that will bring relief from the sapping heat and humidity, though it will ruin daily life in other ways.

A hundred feet down this street, I turn right into an equally narrow (but more peaceful) street. As I walk further into it, the sounds of the market thin out a little. I can feel the air eddying around me, moving more freely. The hot, wet blanket has been taken off.

Ahead of me, to my right, I spot a police post manned by three constables. Two of them are lazing around in chairs behind a large table, while the third is standing with a rifle in hand. On the table, a wireless set is squawking out staccato sounds, interspersed with static.

Across the door from the police post is a shabby yellow building with a small blue door marking its entrance. The doorway is short enough to make many people stoop to enter, I remember thinking. In response to my knocking, it opens a minute or two later. I don’t know what I had expected, but I definitely did not expect to see a slightly shriveled, reed-thin man with a gaunt face and bent shoulders. Hoping that my surprise did not show on my face, I step in and introduce myself. He grunts in response, turns and walks inside. I take that as a cue to follow him.

My eyes wander around the tiny compound, taking in the hand pump, the stairs leading to the adjoining building (which could be where this man lives, I speculate) and the small courtyard separating the gate from the building into which he is now leading me. Not a single tree or plant, I note, disappointed.

The gaunt, thin man turns out to be the caretaker of the synagogue. I have forgotten his name (a pity, but then, I am bad with names), but I will call him Sam in this piece. Short for Samuel, which is as good a Jewish name as any. Sam is befitting, also because it is the name of the person who built this synagogue nearly two and a half centuries ago – Samual Diwekar.

Sam leads me up four steps into a small verandah, where a mesh screen is keeping away the blinding sunlight and bringing in a semblance of cool. A Marathi newspaper is lying open on a reclining chair.

‘Not many people come here anymore’, he says. ‘Service is held only on Saturdays.’ After a pause, he goes on with a wistful glimmer in his eyes ‘But earlier, it wasn’t like this. This place used to be crowded, with people coming and going. Many services used to be held those days.’

I had been so mesmerized by the faraway look in his eyes, that I had forgotten where I was for a moment. His mention of services past instantly recalls me to the present. I remember that I have finally traced the oldest synagogue in the city of Mumbai, a synagogue that was built in 1796. Who would have thought that deep in the bosom of this city lay a building of such historic and cultural value? A building that was the temporal centre of a once-thriving community, that now seems to be counting its last days in India.

And in a way, Sam is the live-in custodian of this cultural heritage today. The lines etched deep on his face, his furrowed brow, his bony frame and the cap perched atop his pate are all still vivid in my memory. As is his slightly melancholic look, his rheumy eyes and mournful tone.

I can imagine him staying in this building almost the whole day, every day, hardly stepping out other than to buy certain essentials. Would he be getting any social visitors at all, I wonder? And what about family? There is something about Sam that hints that he is a loner, withdrawn from the world. Whether he actually is one or not, I don’t know. But stray phrases he lets drop over the next hour only emphasize this feeling.

I speculate that Sam’s personal frame of mind mirrors that of the entire Jewish community in India. Once a large, thriving community, they have now been reduced to a few clusters here and there: in Mumbai, Thane, Pune and Kerala, for instance. While the last remaining Jews of Fort Kochi in Kerala have entered the pages of tourist guidebooks, those in Mumbai have escaped that attention. Indeed, when I was trying to trace this synagogue, I found that most people I asked (even locals and frequent travelers to this city) didn’t know of its existence.

Sam takes me around the medium-sized prayer hall. He points out the tiles, the wooden benches and the polished, old-fashioned lamps hung from the ceiling. Wooden shelves have been ranged along the walls and contain manuscripts, religious texts and various other things associated with running a synagogue. Right in the middle of the room is the Bimah, the raised platform akin to the pulpit of a church, from which the Rabbi reads out the Torah, the religious text. The hall has been maintained well and the floor polished to a shine, though there are small signs of structural decay on the walls. I spot the Torah resting on a tabernacle.

Finding the atmosphere utterly peaceful, I sit down on one of the benches in meditative silence. A few minutes later, I step out of the hall and into the tiny porch, to find Sam deep inside the Marathi newspaper. Not much of a talker is he. He answers my questions in fits and starts, his talk punctuated by grunts and silences. But he does unspool for me the story of this synagogue, the oldest in Mumbai.

It is a curious fact that the Jews of Mumbai have Tipu Sultan, the erstwhile ruler of Mysore and a devout Muslim, to thank for this place of worship.

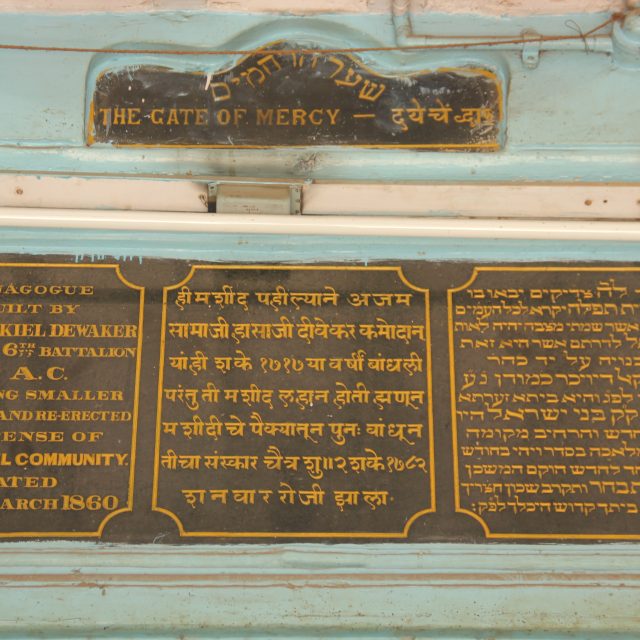

Back in the late 18th century, Samuel Diwekar and his brother Isaac were captured by Tipu Sultan’s troops in the Anglo-Mysore War. Just as they were about to be condemned to death, Tipu asked him which religion they belonged to. On hearing that they were from the Bene Israel community, Tipu’s mother asked him to pardon them because she had read about this community in the Koran. Tipu let them go unharmed. The brothers Diwekar returned to Mumbai and built this synagogue as a gesture of thanks to the almighty. Which is why they named it ‘Shar Harahamim’, which translates to ‘gate of mercy’ in Hebrew. In Marathi, it is called ‘Dayache Dwar’. The synagogue had originally been built in the Esplanade area, but was rebuilt in its present location in 1860. Fittingly, this street has been named Samual Street, as a nod at the good soul who gave the local Jewish community a prayer house.

Sam gives me another nugget from (recent) history. Apparently, the locals have always had another appellation for the synagogue – one that is easier on the tongue and far more colloquial. They simply called it ‘juna mashid’ or ‘juna masjid‘ (meaning ‘old prayer house’ in Marathi, the primary local language). And when the Central Railway authorities wanted to name a railway station they had built nearby, they didn’t have to look far. They promptly named it ‘Masjid Bunder’.

Over the years, most of the Bene Israel Jews migrated to Israel. Others went further West to settle down in the USA. Yet others have co-mingled beautifully with the locals of Mumbai, taking Maharashtrian surnames and speaking Marathi well. Only that they continue to be ardent Jews, professing their faith quietly within the confines of their homes and their last few prayer houses such as this one.

Much like Sam, the keeper of an entire community’s memories and its cultural legacy. Sam, who has built his own little world within the confines of the synagogue.

Fact file

- To reach the synagogue, take a Central or Harbour Railway local train plying towards CST (Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj railway station, also known as VT). Get off at Masjid Bunder station, which is the one before CST. Get out of the station on the Eastern side (or ask someone to direct you to Samuel street or the synagogue itself). Samual Street is a 5-minute walk from the station. Turn into Samuel Street and look out for a faded yellow building with a bright blue door. It actually looks like a house. That is the Shaar Harahamim synagogue.

- This neighbourhood is known as Mandvi. Like I have said in the post, be prepared to walk through a crowded, noisy market. 🙂

- You can also spot the synagogue by the six-pointed Star of David on the building.

- Since certain Jewish establishments in Mumbai were attacked in 2008, this synagogue has been provided police protection. So, don’t baulk at the sight of armed policemen sitting in a booth/tent opposite the synagogue. If they ask you questions, just say that you are a tourist come to visit the synagogue. Show them your photo ID.

- Dress conservatively, since this is a place of worship. No shorts or short skirts.

- At the synagogue, keep your voice low (again, because it is a place of worship and also because the caretaker feels uncomfortable with raised voices. Remember, he lives here in silence for practically the whole week, week after week.).

- Inside the synagogue, you are free to walk around or sit down on one of the benches. However, please do not touch any of the artefacts or religious objects.

- Bombay (Mumbai) is very hot and humid from March to June, after which the monsoon kicks in and the roads frequently get flooded. The best time to go, therefore, is between September and March.