It was a Sunday like any other. But a run like no other.

________________________________________________________________________________

It is 6:30 am on a cool Sunday morning. I take a deep breath and look around. I see a hundred other souls like me, most of them kitted out in T-Shirts, track pants or shorts and shoes. Some of them look bleary-eyed, but the rest are on their toes already, limbering up for the run that is about to start. The place is mostly dark, but the area where we have assembled is awash with light.

The MC is on stage, talking about the run – how this run route is different from conventional routes, what to do after the run is over, etc. She then takes the assembled crowd through a basic warm-up exercises. Most people seem to be in their twenties, thirties or forties. But, I spot a few senior citizens too. One lady in particular catches my eye. She seems to be in her seventies, a little frail and slightly bent with age. She is wearing a saree, but her feet are shod in running shoes. She is accompanied by a couple of much younger people – her grandchildren, perhaps? I salute her spirit inwardly as I do my stretches.

And then, it is time. All of us move to the starting point, where a chorus of girls starts an enthusiastic (and screechy) countdown. …4,3,2,1….and GO.

Slowly, like vehicles responding to the changing traffic signal in a city, we start moving. One foot in front of the other, nudging, weaving, avoiding other feet. The crowd, which initially moved as a single block of humanity, starts breaking up a little distance ahead, as the runners start hitting their stride. The first flush of pink dusts the horizon.

The more serious runners take off at a reasonably high speed, leaving the rest of us behind. Many others (the in-betweens) are running more leisurely. And bringing up the rear are the laggards, including yours truly. Honestly, I am not here to run a timed race, eager to better my previous best and put my fitness to the test. I am treating this more like a pyjama party. And I have dressed the part too – in blue-and-white checked pyjamas, a regular T-shirt and a pair of very frayed walking shoes. What’s more, I am going to run with my camera in hand; probably the only person here who will do so!

My main agenda in coming on this run is to catch this beautiful place at a very early hour in the morning, see some of the parts that I did not see in my previous visit here and take some photos in the soft daylight. This is something I have always wanted to do, but I am hoping that the tag of a ‘run’ and the presence of a few hundred other people will motivate me to get off the starting blocks so early in the morning.

After all, it is not often that you get a chance to run through the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Hampi, taking in the beauty of its medieval ruins in the first light of the day.

I shuffle my feet and trot slowly round the first bend in the route, saluting Lord Virupaksha who is on my right. Even at this early hour, the temple is thronged by several devotees and tourists. By the time I climb the incline next to Kadalekallu Ganesha, I am huffing mildly. I stop and take a couple of photos of this small shrine, as the first rays of the sun fall on it. I marvel that it is so well preserved, inspite of being 500 years old. The slim stone pillars contain carvings that depict day-to-day life from those times.

From here, the run route hangs a left and then a right, taking you past the Krishna Temple (also built in the 16th century). The rising sun lights up the temple’s finely-carved entrance. It seems to be in fine fettle, considering its vintage, though some restoration work is going on. Historians believe that an idol of Balakrishna was brought from Orissa and enshrined here. Across the road from the temple, the long, multi-pillared pavilion of Krishna Bazaar makes for a dramatic vista. I simply have to stop again to take in the beautiful scene. Those days, Krishna Bazaar was the groceries market. I am to learn later that Hampi had many such bazaars – including, unbelievably, a paan supari bazaar. As other runners breeze past me, I shoot a few frames of the temple and bazaar. I don’t know how long I stand there, thinking back to the time when this place must have been teeming with people. I wonder if they too haggled with sellers, like their modern-day argumentative descendants.

Next, I come upon the small, yet beautiful Chandikeshwara Temple. The animals (they seem to be lions) carved into the pillars of this temple look splendid in the soft light of the morning. The inner parts of the temple are in deep shade, but I can make out long cracks in the structure at various places. This temple is unusual, because it is one of the few in India that is dedicated to a form of Vishnu called Tiruvengalanatha. I take a few snaps and move on.

At the next bend lies another small temple with whitewashed walls – the Uddana Virabhadra temple. The whitewash is uncharacteristic of Hampi (where almost all the old structures are made of granite) and so, gives the temple a distinctive appearance.

A short distance ahead, the road passes under a stone gateway. Running under it, I emerge on the side and almost stop in my tracks when I spot several lush, green plantain trees. In fact, a whole grove of them. I am pleasantly surprised. I had never imagined finding even a patch of greenery here, in this ancient capital of the Vijayanagara empire. I wonder why all the photographs of this place show only large boulders and ruins of stone structures.

As I run, I keep sighting boulders and the ruins of centuries-old structures on both sides of the road. Many of these fabulous structures were ravaged by Muslim marauders of the time (such as the Bijapur Sultans); the rest have been eaten away by time and the elements. I wonder how beautiful these monuments would have looked in their full glory. I feel sad as I think of the destruction wrought on such beautiful works of art. As things stand, we are left to gaze at their ruins and find beauty in their decay.

I rememeber thinking at this point that Hampi perhaps has the distinction of having the maximum density of ruins and boulders per square kilometer in the world. ‘More history per square inch’ will make a good tagline for this place.

By now, my run has turned into a full-blown quest for ruins. Though I have been here once before (a few years ago), I did not visit some of these parts back then. And so, I am full with a sense of discovery.

Unlike the other runners who are focused on the road, I keep looking to my left and right. I don’t want to miss the beauty of the route, you see? My mind is like a sponge, soaking in the sights and sounds I encounter along the way. Running with the camera does slow me down a little, but I don’t mind. I see a few other runners raise an eyebrow on spotting my camera and then smile broadly, as understanding dawns.

A short distance ahead lies another shrine – this one dedicated to Lord Anjaneya. Finding an ascetic at this shrine of the monkey god, I stop to have a few words with him. He tells me that this particular Anjaneya is believed to be all-powerful. ‘Pray here and your wish will definitely be granted.’ he tells me in Kannada. He graciously allows me to take his photograph before going his way.

This stretch of the run route is flanked by paddy fields, with the rice paddies growing to more than six feet. I am huffing again, and so, stop at a culvert to catch my breath. A small stream rushes by at the culvert. I take in the fresh air and marvel at the lushness and serenity of the place.

Soon after I resume running, I come upon a fork in the road. The right turn leads to Hospet (and seeing how desolate it is, it seems to be the road less taken), while the road ahead is the run route, going towards Kamalapur. Bang at the fork, a motorcycle is parked with a policeman sitting astride it. I wave at him and say ‘Namaskara, sir’ and he waves back. As I continue running, I spot a woman, a man and a boy walking together ahead of me. The lady is goading the little man to keep running. I catch up with them and say ‘hi’. The boy, all of six years old, is wearing a T-shirt that proclaims him to be ‘Adi’. Along with him are his mom and uncle. Apparently, his dad and aunt are running the 12 km stretch. I do my bit to motivate Adi to resume running – ‘Look, you have been ahead of even me so far. And if you keep running, you can beat me to the finish!’ After some nudging and cajoling, he resumes jogging. I mentally doff my hat at the child, who is sportingly running 5 kms over undulating and unfamiliar terrain. Talk of getting out of one’s comfort zone.

I want to run along with Adi, but I can’t. I have just spotted something intriguing and must know what it is. I see a cluster of stone slabs to my left. A closer look reveals that they are a set of roofs in the middle of a patch of green. I walk around the fenced area and find a small gate. Entering, I find steps going down to a temple. A board proclaims the site as that of a Shiva temple, lying totally underground. It is easy to miss this temple from the road, if you don’t look carefully or didn’t know about it already. This temple is sunk about 15 feet below ground level. Inscriptions found in the temple refer to it as the ‘Prasanna Virupaksha temple’, seven hundred years old. King Krishnadevaraya is said to have donated a lot of money to this temple at the time of his coronration. Today though, many pillars have fallen and stones dislodged. The walls are cracked and the corners, chipped. And yet, the temple is strangely beautiful. I can see that the halls, pavilions and sanctum sanctorum have been crafted with great love and skill.

I spend about 10 minutes taking in the place, before I run on. I am now on an upward incline on the road. To my right is what the locals refer as the ‘akka thangi gudda’ (‘Sisters boulders’ in English), a couple of mammoth boulders that seem to be conjoined at the head. Across the road from me, I spot two runners on the return leg of the run. Thinking that I am losing steam, they dole out some pep talk. ‘Don’t lose heart, buddy. Keep going. You are nearly there.’ says one of them. ‘You don’t know the half of it’, I mumble, but smile back at the well-meaning gesture.

Cresting the incline and turning a sharp bend on the road, I see that I have reached the turn-back point. The half-way mark on the run. A few other runners are clustered here, helping themselves to the bananas and biscuits that have been laid out on tables. A volunteer is serving water. I can see smiles of relief and relaxed faces. They must all be happy that at least half the distance has been covered.

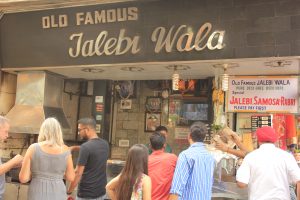

I suddenly realize that I am famished, and wolf down a couple of bananas and a few biscuits. As I am making small talk with the volunteers, Adi, his mom and his uncle also join us. A few minutes later, it is time to start my return journey. This leg of the run is quicker, because I don’t stop to click photos. Curiously however, it also seems easier than the first half. Almost before I realize it, I spot the Virupaksha Temple and a few minutes later, I am at Hampi Bazaar, the starting and finishing point.

Rajesh, my friend, has finished ahead of me and is waiting for me here. The place is teeming with people again, many of them clicking the mandatory selfies. I move to a quieter place, take several deep breaths and look back on the run – the sunrise, the beautiful ruins, the greenery, the ascetic, the underground temple. I have seen some parts of Hampi that I missed on my earlier trip to this place.

Physically, I am a little tired, but mentally I am fully refreshed. It feels like I have done myself a favour by participating in this run.

Show me some love. Like and share this post.