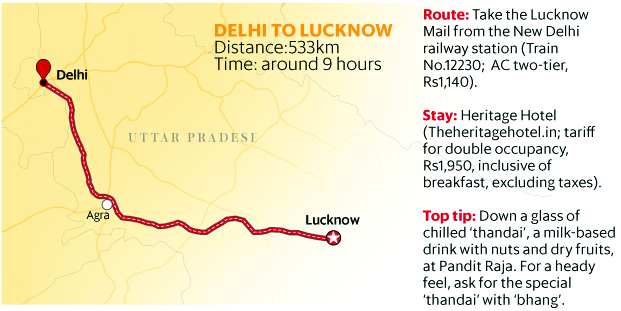

Hidden in the labyrinthine lanes of Old Delhi are some of the best food spots of the city. They are high on history, taste and atmosphere.

________________________________________________________________________________

The mere mention of Old Delhi conjures up vivid images of a crowded bazaar (traditional market), old buildings from the Mughal era and wonderful, aromatic food. Take away even one of these elements and the Old Delhi picture will not be complete.

For me, Delhi is home because one half of my family lives there. So, while I live in Bangalore, I definitely end up making a ‘family pilgrimage’ to Delhi at least once a year. During my trip in October 2016, I took time off to explore the streets of Old Delhi. I was especially interested in the decades-old eateries that have been Old Delhi’s pride. In fact, many of them were set up in the early 1900s, making them nearly a century old. Some others are about a hundred and fifty years old and counting. With so many years behind them, you are talking serious history. Each of these joints has secret family recipes that have been handed down from generation to generation. Every one of them also has one or two signature dishes that they claim will beat competitors hollow. Facts like these add to the allure of these eateries. No wonder then, that they accumulated a large number of loyalists much before social media popularized the concepts of fan base and followers.

Make no mistake, given the character of Old Delhi, these eateries are all dives. Nothing fancy when it comes to ambience here. People throng them only for the taste of their food, their history and the ‘atmosphere’. Without much further ado therefore, let’s attend to business, shall we?

Nathu Ram Kachoriwaala

We got off the metro at Chandi Chowk and exited the station through a narrow gully (lane) that leads deeper into the Chandi Chowk market. A couple of minutes later, we spot a Hanuman temple and right opposite that, under the shade of a large tree, is Nathu Ram’s food stall. The ‘stall’ is actually a large tarpaulin sheet that has been spread under the branches of the tree. Cooks are at work under the canopy, one frying jalebis, another frying kachoris. A couple of attendants are helping the cooks out. A few rickety wooden tables stand desultorily, with customers gorging from small, stitched-leaf bowls known as donney in Hindi.

Nathu Ram has been feeding hungry souls for more than seven decades. Nobody (including the guy at the counter) seems to know exactly when it was set up. Frankly, nobody bothers. What they do bother about though, is the food that is being doled out.

While the menu nailed to a wooden pillar announces a dozen dishes, most customers ask for one thing first: bedmi puris. We do the same. A couple of minutes later, we are handed out donnays with piping hot, crisp puris, accompanied by aloo subzi (potato curry). Bedmi puris are palm-sized fluffy breads made from whole wheat flour (atta). The dough has been infused with spicy lentils and asafoetida (known in Hindi as ‘heeng’). The aloo subzi has small pieces of potato in a spicy, watery gravy. I have had this subzi at various places in North India, but the variant found in Old Delhi has a unique taste and flavor.

Given the size of the puris, we nail several before drawing a deep breath and taking a break. We are sweating profusely, partly because of the heat, but also because of the spice in the food. Talk of being in sweaty heaven(exclamation).

A pair of puris with unlimited refills of aloo subzi comes for Rs. 24/-. If that isn’t cheap, what is?

Kanhaiyalal Durga Prasad Dixit

Next, we wend our way to Gali Parathewali (Hindi for ‘paratha lane’; making it amply clear as to what life here is all about), which lies a short distance away. On the way, we pass Shishganj Sahib, a famous gurudwara.

The history of Gali Parathewali goes back nearly two centuries to the mid-nineteenth century. Though the character and complexion of this street has changed considerably over the decades, a handful of the old eateries remain. They are each run by the sixth or seventh generation of Brahmin families from Uttar Pradesh (especially, the Allahabad belt), a fact they take great pride in. It is to one of these that we head this morning.

‘Kanhaiyalal Durga Prasad Dixit’ announced a large board at the entrance to the humble eatery. The fact that it was set up in 1875 is mentioned prominently. The insides of the eatery have been jazzed up a little with lights that are too bright. The cook is at work near the entrance, making – what else – parathas. You can play safe by asking for the regular aloo, gobhi, methi and mooli parathas. Or, you could get adventurous by ordering one of the more intriguing variants: nimbu, gajar, mutter, papad, kela, karela, tamatar and mewa.

Our gastric juices start flowing again (never mind that we have just stuffed ourselves with puris). We seat ourselves and order three plates of parathas, which arrive a few minutes later. Each plate comprises two small parathas, accompanied by three curries and some pickled vegetables. Everything on the plate is delicious. We polish the food off in no time, before ordering a few more plates. The parathas are crisp and stuffed well with the vegetables of your choice.

A plate of parathas sets you back by about Rs. 60 or 70, depending upon the variant you choose. The price is steep, but worth it, considering the wonderful taste and the fact that you get repeats of the accompanying curries and pickle. Parathewali gali is somewhat overrated, but still worth a visit once in many months.

Pandit Gaya Prasad Madan Mohan

Deciding that our tummies needed a respite after that overload of puris and parathas, we walk a few paces from Kanhaiyalal to Panditji’s hole-in-the-wall that serves luscious rabdi and lassi (to be explained). The lassi (thick, sweetened, churned curd) comes in a tall, stout steel tumbler, while the rabdi (thickened, sweet milk topped with a thick layer of cream) is served in a small bowl made (oddly) of aluminium foil. While lassi is available in most parts of India these days, you must have it in North India, especially in Punjab or Old Delhi, to savour it in its full, authentic glory. It is refrigerated and served chilled. The drops of moisture on the outside of the steel tumbler could well we a reflection of your thirst.

Our thirst slaked and the fire in our tummy doused for the moment, we took a stroll through the Chandni Chowk market with its small, old shops and pavement hawkers. Cycle rickshaws and autos deftly wove through the congested thoroughfare like only they can.

About an hour later, we were ready for our next gastronomical foray. And that’s how we landed up at Kanwarji’s Restaurant.

Kanwarji’s Restaurant

You can’t go to Old Delhi and return without having had the chholey bhaturey. Kanwarji’s Restaurant is a narrow outlet, with sweets arranged in shelves right at the entrance. You can take one of the few seats laid out inside or opt to stand on the pavement and enjoy your food. We choose to do the former.

Chholey bhaturey are as much a part of Delhi’s culture as the Red Fort and India Gate. If you ask me to single out one dish you should have on your next trip to Delhi, I would recommend this dish without batting an eyelid. Every area of Delhi has several joints serving this staple, and each has its own taste and flavor.

As if to demonstrate this point, the bhaturey at Kanwarji’s are oval (you get them round everywhere else). The dough of the bhaturey is infused with a mild mixture of asafetida and something else that I could not quite place. The chholey is a dark brown slurry, with chickpeas (channa) floating in it. Onion rings and pickled long green chillies (which are staple accompaniments to dishes in Delhi) complete the ensemble.

I am recalling all these details for you in retrospect now. At that time though, we just waded into the food. The next time we looked up was fifteen minutes later, after we had picked our plates clean. After that, all we could do for the next few minutes was sit back and sigh in deep contentment.

A plate of chholey bhaturey here comes for Rs. 60/-.

Pandit Mittanlalji Lemonwaley (aka Mittanlalji Bantawaley)

Banta, as it is known to locals in Delhi, is lemon soda to which a pinch of black salt has been added for that tangy twist. It is much sought-after as a great refresher in the torrid climes of Delhi. A reasonably tall glass of cold banta comes for Rs. 15/-. Since the shop (like all other shops in Chandni Chowk) is actually a crevice on the old wall, there is no shade to stand under. Gulping down the cold drink standing in the glare of the hot sun is an interesting experience.

Natraj Dahi Bhalla Corner

And now, for some famous dahi bhalla. Located at the mouth of a lane that leads to Chandi Chowk metro station, Natraj has been dishing out dahi bhallas since 1940. A bhalla is a fried, sour ball of gram flour. After it is cut into small pieces, onto which fresh, thick curd is poured. This is then topped up with generous doses of green chutney (made from crushed mint leaves) and khatti-meethi chutney (sweet-sour chutney made from tamarind) and served to you. I shovel a piece of the bhalla into my mouths and feel a soft explosion of flavours hit my palate. By now, it is well past noon and the sun is high up. Thanks to our prolonged culinary assault since morning, our stomachs are bulging and our knees buckling. We are tottering on the pavement. Much as we’d love to have a second helping of the bhalley, we are forced to keep that for another day.

For now, we just want to head home and crash. But before that, one last stop.

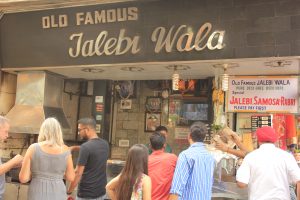

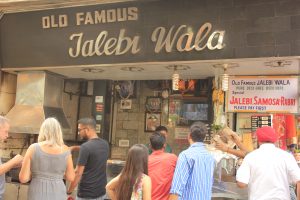

Old Famour Jalebiwala

Several decades ago, Dariba Kalan was famous throughout Delhi for its goldsmiths and jewellery shops. Though many of them remain in business, many others have shut shop. At the entrance to this narrow lane is a shop whose business has nothing to do with gold or jewels. Welcome to Old Famous Jalebi (heck, I am not using these words as adjectives, but as a proper noun. This is the name of the shop, you see?) When your outlet is old and famous, why complicate matters by naming it anything other than ‘Old Famous?’ The shop has been around since 1884.

Thick juicy, golden-coloured rings of fried batter lie in trays, waiting to be bitten into. A pot-bellied cook is taking out fried maida rings from the cauldron and dunking them into a large vessel containing sugar syrup (known as ‘chashni’ in Hindi). A crowd of about fifteen is jostling for space where there isn’t any. Here, you have to pay first and then take your goodies. Not being in any shape to eat them there, we ask them to pack a kilo of jalebis for us.

We will enjoy them in the comfort of home, sprawled on comfortable beds. And then promptly go on the blink.

The vitals

- Old Delhi is a city within a city, a world in itself. In its warren of narrow streets are several food joints like the ones I have described above. One trip is not enough to do full justice this area. You could therefore make a beginning by visiting the above-mentioned eateries and then come back another day to continue your culinary sojourn. After my next visit to Delhi, I will upload Part 2 of the Old Delhi Food Trail.

- By and large, most eateries here are open from 8 am to past dusk. You can therefore visit any time in between. The trail I have described here took us about four hours to complete at a leisurely pace.

- Just keep the heat of the city in mind when you plan this trip. The temperature stays above 40 degrees Celsius for most of the year and the humidity is high.

- The best way to go to Chandni Chowk is by the metro. Taking along a private vehicle would be a bad idea, because you won’t get a place to park. This area is congested with a capital C.

Show me some love. Like and share this post.

![]()